#43 – Dick Bernard: Fathers Day

Happy Father’s Day to all you biological Dads, and the legions of “Dads” whose role was defined by other than physically being the parent.

Being “father” is a complicated business that defies simple definition. Even defining my own assorted roles over the 45 years since I first became a father in 1964 would take a lot of words: and that would only be my own descriptions from my own perspective. Suffice to say that I am with experience in the business of trying to be “father”; all of those who have experienced me as “father” at any point along the way would have their own interpretation of whether I was a good Dad, or a lousy one, or all shades in between at one time or another in each relationship.

That is how the role “father” is. It is pretty hard to make a “sound bite” of what it is to be “Dad”.

Over the years I’ve watched a lot of men, (and women), practice the imperfect art of fatherhood, juggling it with all the assorted roles that come along with the job. Each of us have similar stories, having lived the life, or watching someone else live it. Each story is unique and really never ends. In many ways we are, good and not so good, a reflection of who we watched and experienced over our lives.

My “poster child” for this Father’s Day 2009 is my great-grandfather, Denys-Octave Collette. I’ve picked him because his is the earliest real photograph I have of an ancestor. It is an old tintype that I still have. That photograph is at the end of this piece.

Octave, as he was apparently called, was born in rural Quebec in 1846, and when he was about 21 the entire family, parents and siblings, moved west to St. Anthony, the original white settlement at St. Anthony Falls, which a few years later became part of Minneapolis MN. He was not his father’s first child, but he carried his father’s name for some reason. That Dad went by Denys for some reason.

In 1868 Octave married my great-grandmother Clotilde Blondeau at the Catholic Church of St. Anthony of Padua in St. Anthony MN, only a mile or so from historic St. Anthony Falls. Her Dad was a French-Canadian voyageur, and (almost certainly) her Mother a native American from Ontario. The Blondeaus, already with a young family, had somehow or other come to what is now suburban Minneapolis (present Dayton) not long after 1850, long before there were railroads or roads to this area.

In 1878, Octave, and several of his brothers, “walked”, it is said, to homestead some ground on the Park River at Oakwood ND, a village just to the east of later-founded Grafton, and a few miles west of the Red River of the North. The description “dirt poor” probably well describes them.

From the union of Octave and Clotilde came ten children, including my grandmother Josephine. Several of the children died young, as was not uncommon in those times. Their entire married life they lived on the same farm, doing their best.

Great-Grandma died in 1916. Great-Grandpa remarried the next year to some mysterious woman in Minneapolis. I say “mysterious” because she apparently did not pass whatever test was administered by the family for acceptability…I know her name and when they were married and where, but she doesn’t merit even a footnote in the family annals. Had my Dad not “spilled the beans” about her, I probably wouldn’t know she existed.

She died in the early 1920s in Minneapolis. They had a small store (which still exists as a corner store) on Lyndale Avenue at about 36th Street in North Minneapolis. Their home exists now only in memory, somewhere above the cars which enter Minneapolis bound I-94 at the Dowling Avenue ramp.

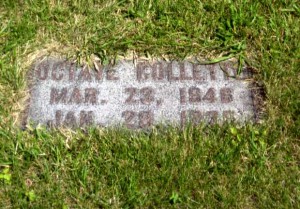

Octave died a year or two after his spouse at what was called the “poor farm” in Winnipeg (doubtless there’s a story there, too). He came home to be buried next to his first wife and two of their children who had died in infancy in the churchyard of Sacred Heart Church in Oakwood ND. He resides there to this day, roughly a half mile from where he farmed for the first 40 years of Oakwoods existence.

I’ll be at that still-surviving church and churchyard about noon on July 17, along with a tour group who is revisiting French-Canadian, and intercultural relationships between the whites, native Americans and Michif (“half-breeds”) at Turtle Mountain in Belcourt. We’ll be exploring relationships….

Thanks for the memories, Great Grandpa.

Octave Collette and Clotilde Blondeau - 1868 - Minneapolis MN

Update: July 11, 2009

Monday we head north from the twin cities area for a short vacation. On the 15th we will be in Winnipeg to visit relatives on Octave’s side of the family; on the 17th I will be in Oakwood, at a luncheon in the church which Great-Grandpa Octave helped to found in 1881, near which he lived and farmed and raised a family for nearly 40 years, and in whose churchyard he is buried. The next few days will be an opportunity to revisit family history.

The original post, above, began normally enough, about a Father on Father’s Day. But Octave’s life ended unpleasantly, with family friction and dilemmas resulting in his dying on a “poor farm” (rest home) in Winnipeg; and his grave in Oakwood un-marked for well over 50 years.

As it goes in families generally, exposure of “dirty laundry” is not always appreciated as it appears to sully the family reputation. Such is what happened in this post, though in a very innocuous manner. On the day this post appeared, one descendant, a cousin of mine, wrote me with a story of why the Canadian kin did not harbor their kin in his last unfortunate years. “he had been [at his sons house] for only a few days and fell down the stairs [and they couldn’t take care of him]. [Two of the sons] wanted to have him buried with their mother in Oakwood. [One] had a large family and could not afford to bring his Father to Oakwood. [The other] was able to scrape together enough money to bury his dad with his mother in Oakwood.”

But there was more to the story, most of which will never be known, but some of which was filled in by my Dad in 1981.

Octave was part of a large family, and all of his siblings moved to the Oakwood area about 1880, and by the time of his death, there were lots of descendants and relatives in the area between Oakwood and Winnipeg. Nowhere was there “room in the inn”.

In 1981, my father wrote about the situation: his mother, Octave’s daughter, could not take in her Dad because their house was too small and she still had three kids living at home. Octave’s son, who had received the farm from his Dad a few years earlier, perhaps could have, but his new spouse was not especially excited about the prospect of having an aged relative she hardly knew living with them. Hers was likely a very reasonable concern.

Many other siblings and kinfolk between Minneapolis and Winnipeg existed, and all likely had similar and perfectly logical stories. They had not planned for Octave coming home.

I leave the last word to my own father, Henry Bernard, who was Octave’s grandson, and was a teenager when the family drama took place. After I noticed no headstone at Octave’s grave in 1981 I asked my Dad to tell me what he knew about the story, and he did, in two letters dated June 29 and July 13, 1981. Parts of this essay reflect what he remembered.

Two short portions of his story, in his own words, seem pertinent to end this essay: “No marker was ever put for him [on his grave] for some reason. There were stories about that but I don’t think it is pertinent.” (No one has subsequently “spilled the beans” on that tantalizing morsel!)

He neatly sums up the story, thusly: “The comments reveal the reality of all families – that not all is perfect, and in fact it is unreasonable to expect perfection….”

Here’s to families, with all their warts and imperfections! We do the best that we can do.

Update July 23, 2009:

I visited the “scene of the crime” July 16, 17 and 19, and perhaps have what will be the last words on this topic.

July 16, in rural Manitoba, I visited with Agnes, recently turned 90, who is Octave’s granddaughter, lived in the house with Octave, and was 5 years old when he took the fateful tumble which led to his hospitalization at the “Poor Farm” in Winnipeg sometime before his death in January, 1925. Agnes remembered Octave as a man with white hair who walked the farmyard with his hands clasped behind his back. In the directness that accompanies being 90, and reflecting the innocence that accompanied being 5, Agnes said that when she saw her Grandpa fall down the stairs, she laughed – she thought it was funny (her Mom quickly straightened her out!) As she was recalling the event I remembered that a number of years ago my Dad and I had stayed in the same house, and we had come down the same stairs as Octave had that fateful day many years earlier.

I also remembered an incident when I was less than 10 when I, and a bunch of other boys, witnessed my own father taking a wicked tumble down a stairs. None of us paid much attention to his agony – we were playing basketball, and that was more important. Thankfully, Dad got up and wasn’t hurt (he was perhaps 40 at the time). Hopefully, if he had been hurt, one of us would have had the common sense to get some help for him. Kids often don’t tune in to these kinds of things.

The day after the meeting with Agnes, I was in the churchyard where Octave remains buried, an appropriate footstone now marking his presence.

Octave Collette R.I.P March 23,1846-January 25, 1925

Two days later, Sunday, July 19, several of us went to the site where Octave had died, next to the St. Boniface Cathedral in Winnipeg. By now, I was hearing the “Poor Farm” more accurately described as a Hospital or Hospice; a caring place staffed by the Grey Nuns. The original hospital had been replaced by an impressive new hospital on the same site as the old. In those old days, it was not uncommon for elders to spend their last years in a hospital room. In fact, Octave’s daughter, my grandmother, lived her last several years in such a circumstance in her North Dakota town. She died in 1963.

Octave has long rested in peace; now I can rest as well, knowing (I think) most of the rest of the story. I still have curiosity about Octave’s second wife and her sons: I know the unusual surname, and actually saw it on a billboard while in Canada, but whether I will actually pursue that angle or not is an unanswered question.

It has been an interesting search.