The Chicago 7

Last night we decided to watch “The Trial of the Chicago 7” on Netflix. It was a choice I’m glad I made; an opportunity to visit (for the first time) the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, which led in turn to Hubert Humphrey as the nominee for president, and the ascent of Richard Nixon to the Oval Office in the November election. There is a great plenty of information available about this time in history, so I don’t feel a need to make a recommendation.

The Trial of the Chicago 7, released in Oct, 2020, before the 2020 election, is excellent. Of course, all films, are like all novels: not all ‘facts’ are necessarily facts. This film is no different. The trick is to get the essentials of the story correct…and “The Trial of the Chicago 7” does that, including period film clips. It’s worthwhile digging deeper into the story.

If you haven’t seen the film, do. It’s a Netflix film.

I was 28 in 1968, certainly old enough and politically aware enough to know what was happening in Chicago. But it was not much on my radar, then. To quote myself, from something I wrote in April, 2018, 50 years after: “[I was] “in my third year as single parent of a four-year old son, teaching Junior High…[b]eing an activist was not on my personal radar….” There were many millions of us with infinite variations on the same theme. We saw the news, but didn’t appreciate its significance.

As I watched the film, I found myself thinking of other analogous (my opinion) situations at other times.

Most recently was the January 6 Insurrection at our Nation’s Capitol, as I write, awaiting the trials of hundreds.

Even more recently, the Derek Chauvin Trial here in the Twin Cities, following up on George Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020, has had massive attention.

Further back, I thought of the Nuremberg Trials in the aftermath of WWII. In the same publication which held my quote, above, was a full page by Nuremberg prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz, which appeared in a February 26, 1989, publication. It is worth reading, and accessible here: Benjamin Ferencz Feb 26, 1989.

All four situations reflect law, and conflict over interpretation of Law, and society generally, and anyone even slightly interested is generally aware of each of them. My list could be much longer, but let these suffice.

I have personal opinions about all of these, but my point here is not to argue what is right, or wrong, about any point of view expressed on any of these issues; rather to refresh memory.

I encourage the reader to give some thought to each of these in context with your own particular feelings. And how to reconcile differences to have a civil society, the role of punishment, or reconciliation, or whatever one wishes to mark and resolve differences. How do we build from here?

As I conclude this brief writing, I think back to a memorable quote from Nuremberg Trials which was so unbelievable to me when I first saw it that I had to search it out to its original source. It continues as one of my most memorable examples of food for thought:

“Why, of course the people don’t want war. Why should some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece?

Naturally, the common people don’t want war, neither in Russia, nor England, nor for that matter, Germany. That is understood, but after all it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simpler matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the peacemakers for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country.”

Hermann Goering

Long time Nazi, Reichmarshall, and heir-apparent to Hitler, Statement made while imprisoned at Nuremberg after WWII. Goering was sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes, but committed suicide first.

Quoted in the book Nuremberg Diary, p. 278, Gustave Gilbert, Farrar, Straus & Co., 1947. Gilbert was psychologist assigned to the Nazi prisoners on trial at Nuremberg.

POSTNOTE, same day: My personal thoughts about the four above situations focus, generally, on two aspects. One is the obvious and profound changes in communications technology since my own birth in 1940, even more rapid and profound than in the time preceding my birth. As I write, today, even for someone elder like myself, it is hard to visualize the time before cell phones and ubiquitous detection devices like security cameras and iPhones. What one could hide, before, is virtually impossible to conceal now.

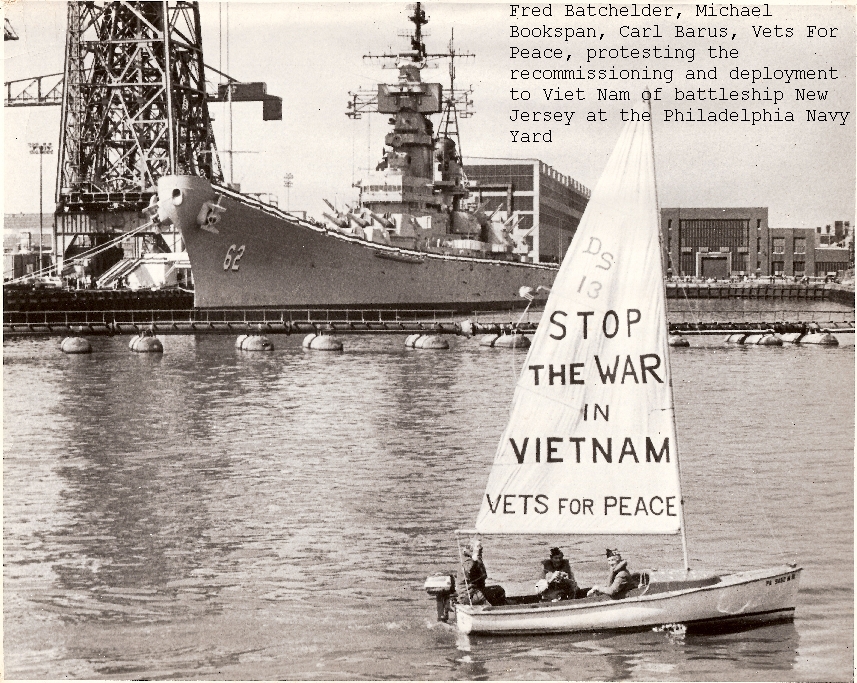

Along the same general lines is the ongoing and ultimately futile strategy of trying to restrict the right to protest. Currently there are many efforts around the states to restrict the rights to freedom of expression given by our own constitution. My guess is that the initiatives, even if passed and signed into law, will be about as permanently successful as was prohibition in the 1920s and early 1930s. The cure was worse than the disease. One can hope for sanity.

COMMENTS (more at end of post):

from Carol: I’m with you – just a handful of years behind you in age and starting my own family in central Minnesota, I wasn’t paying a bit of attention. The civil rights movement seemed like on another planet. Now I can’t believe I wasn’t marching… somewhere.

from Peter: My first thought about your inquiry is what’s taking most of my time these days to get between book covers: we are not in the Information Age anymore. Information does not move the public. They have already been hijacked by spectacle, by the time information shows up. This is a paradigm-level change, like driving your car into a canal. Stepping on the brake is no longer effective or relevant.

In 1968 I and most people I knew were constantly reading and talking about the terrible crime that was the Vietnam War. We knew the true stories behind the false official accounts. We swam in a sea of information, most of it mimeographed (precurser of xerox), sung, spoken, or by snail-mail (the only kind of mail then). By the time something spectacular happened, we already knew the whys and wherefores. Of course that’s all backward now.

I knew about the Chicago events, they were on everybody’s mind, but I was occupied. We were skillfully pitted against our peers, those who went versus those who somehow escaped the draft. And that did not follow political lines, it followed economic lines, as people with more education and money in their families knew how to work the system of exemptions and deferments.

For example, I filed with my draft board as a Conscientious Objector when I was 18, and spent two years working my case up through the courts, expecting to be sent away to war or jail any moment, and four years mopping up after surgeries in hospital operating rooms, to fulfill my “obligation.” I still have my FBI file, somewhat redacted to protect my neighbors and school teachers, although most of them backed my claim. Nobody accused me of cowardice or shirking my “duty.”

I understand George W. Bush had other ways of getting out of it. Somehow our manhood seemed to be involved.

As to the Chauvin trial, the dramatic increase in blatant, on-screen murders by police that accompanied the trial seems like a clear and terrifying message. But there is a subtlety here: while it is clearly an expression of racial bigotry, economic class is the primary driver. Police are recruited from just above poverty, and “serve and protect” social strata they may hope their kids reach someday. Police don’t seem to have faced much union-busting.

Recent studies purport to show that whites in districts becoming more “diverse” express deep fears of being “replaced.” Of course they do: they understand the vast and horrible crime that has been perpetrated by white people for so many generations. That crime was the source of America’s great wealth. The amount of money that goes into sustaining the violent repression and incarceration of people still economically marginalized by race provides a glimpse into the mass-denial we have all lived in for generations.

Had the Chauvin verdict been what most of us expected (i.e., a big middle finger to populations that soon can no longer be called “minorities”), there would surely have been real trouble, far beyond a few smashed windows and burning cars. But the smoldering embers will keep on smoldering until America gets up off Black America’s neck.

Meanwhile, there’s so much money being made, don’t hold your breath.

from Jeff: In regard to Nuremberg, the author and podcaster Malcom Gladwell recently published a new book, The Bomber Mafia, which is about Curtis Lemay and the developers and administrators of the bombing strategy in WWII. I may have advised you to listen to his podcast from last year, 3 parts, on this that he turned into a book. Initially the Allies (USA and UK) tried a precision bombing strategy to destroy military and industrial sites of the Axis (mostly Germany in the early years of the war) but the technology available made getting bombs to targets practically useless. And of course not hitting targets came at the cost of huge losses to Allied air crews. in war sense , the sacrifice of men and planes wasnt worth the results. Lemay and a few others (the Bomber Mafia) advocated what essentially was “carpet” or saturation bombing…big quantities over a wide area , and no consideration of the civilian deaths in enemy territory. (obviously they were working under the threat of Goring’s bombing of Britain which didn’t try to spare civilians, and the torpedoing of unarmed vessels by German U boats) Also they worked with scientists across the USA to develop a better bomb material…and napalm was born. This eventually led to the fire bombing of parts of Germany , and the firebombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities later in the war. Hundreds of thousands of German and Japanese civilians died. (the equation in regard to Japan was that this along with the nuclear bombs, brought the war to an end in summer 1945, instead of perhaps 1 or 2 years later during an invasion of Japan and the loss of millions of lives civilian and military.

from Jermitt: This is a very powerful post. There are so many things I would like to share on each of the “times and issues of these times” relating to my own “education or social development” that your message and the messages of the others brought back into focus. It would require a month or more of writing. In the end, it would be a valuable task, at least for me. Even reading and reflecting on these times has been beneficial to me.

from Dick: Everything I write at this space is meant to be shared.

from Joyce: I was only 17 when the Democratic convention was held; I paid attention to the news, I was in college, and it was talked about everywhere on campus, but since I was way too young to vote (the voting age at the time was 21) I didn’t pay too much attention. I was involved in some Vietnam war protests, and there were a lot of protests against LBJ, and a lot of talk about the “credibility gap”, all because of the war. Still, when Nixon was elected, I was deeply disappointed, but not too worried; the Republican party at that time was not insane, though Nixon was corrupt. I was still very much under the influence of my parents, who were conservative Democrats, thoroughly supportive of the war, and very opposed to the protests. It was only later, years after the events of 1968, that I read about the protests, and the arrests and trial. I found the movie gripping; it made me wish I had been more aware, and more involved back then.

Hello Dick – as always, a thoughtful blog post. As Executive Director of the League of Women Voters of MN, I took a lot of time in 2019-2020 to read and learn about the history of suffrage and the coming to pass of the 19th Amendment. And I was forever touched by the power and perspective of learning our history. In 1918-1920, they had a global pandemic (the major flu epidemic), terrorism (WWI), racial injustice (such as the lynching of the 3 Black men in Duluth), backlash against immigrants (back then, it was the scandinavians!), and of course, voter suppression – women could not yet even vote. Sound familiar? Flash forward 100 years, and similar themes prevail. But what is also true is the incredible strides we’ve made in the last 100 years. More people vote than ever did before, we no longer enslave and lynch Black and indigenous people and a new awareness of racial justice is producing changes in policy in rapid order, we’ve not had a WWIII and overall, violence (though not poverty) is in many ways at an all time low, and we in no way reached the 50 million dead during the 1918 flu. Of course, we have many many ongoing challenges in our day. And rise to meet them, we must, as those before us did and paved the way to all the rights and benefits we appreciate today. But the evidence of history shows us that life for nearly everyone in America and perhaps the world, is better than it was today than it was 100 years ago – except for most indigenous people, who continue to suffer from the destruction of their land and culture. A large number of immigrants are still able to come to America and escape repressive regimes – Look at the Liberian, Somilia and Karen settlements in Minnesota. No, none of it is perfect nor complete. But again – look at even recent history. Trump only served one term. And we elected a Black man to be president for 2 terms. The times… they are a changing as always – 3 steps forward, 2 steps back – but forward towards peace and justice nonetheless. And this is the lesson – Democracy requires us to pave the way for change we may not even see in our lifetime, just as others did for us. So keep on keepin’ on, believing in the power of perseverance and hope and struggle, and not expecting action today to bring change tomorrow. Democracy is about the long game – so get in the boat and row, and appreciate the progress made and the “good trouble” we’ll all continue to get into on the river ahead.